Abstract

Policy change has long been explained through competing theoretical frameworks emphasizing institutions, actors, ideas, or external shocks. However, many existing approaches tend to privilege one dimension over others, leaving the dynamic interaction between context, substance, and process under-theorized. This article proposes an Integrative Model of Policy Change, arguing that policy change emerges from the simultaneous transformation of (1) the macro policy environment, (2) substantive elements of policy, and (3) the processes, interactions, narratives, argumentations, and platforms through which policies are produced and contested. Drawing on policy process theory, interpretive and discursive policy analysis, symbolic politics, and governance literature, the model conceptualizes policy not merely as decision or output, but as an evolving social and discursive process. The article contributes to policy studies by bridging structural, agential, and discursive explanations of policy change within a single analytical framework.

Keywords: policy change; policy process; discourse; narrative; governance; interpretive policy analysis

1. Introduction

Why do public policies change? Despite decades of theoretical development, this question remains central—and contested—within policy studies. Classical explanations emphasize rational problem-solving, institutional design, or shifts in political power. More recent approaches highlight agenda-setting dynamics, advocacy coalitions, or external shocks. Yet, empirical realities increasingly demonstrate that policies often change without clear problem resolution, without major institutional reform, or even without formal decisions.

This article argues that such changes cannot be adequately explained unless policy is understood not only as a decision-making outcome, but as a dynamic process of meaning-making, interaction, and performance. Policies change because the conditions, actors, ideas, constraints, instruments, and—crucially—the discursive and technological arenas in which policies are debated—change simultaneously.

To address this gap, the article proposes an Integrative Model of Policy Change, synthesizing insights from multiple strands of policy theory into a coherent analytical framework.

2. Positioning the Model within Policy Change Literature

The study of policy change has produced several influential frameworks. The Multiple Streams Framework (Kingdon, 2014) explains how problems, policies, and politics converge to enable agenda change, but offers limited insight into post-decision dynamics. The Advocacy Coalition Framework (Sabatier & Weible, 2014) foregrounds belief systems and coalitions, yet tends to underplay symbolic and performative dimensions of policy. Institutional approaches emphasize rules and structures, but often struggle to capture rapid, discursively driven change.

Parallel to these developments, interpretive scholars have advanced a discursive turn in policy analysis. Hajer (1995) conceptualizes policy-making as an argumentative process, Fischer (2003) emphasizes deliberation and interpretation, while Edelman (1988) demonstrates that policies function as symbolic actions shaping political meaning rather than merely solving problems.

However, these strands are rarely integrated into a single model of policy change. As a result, policy change is often fragmented analytically—explained either by structures, actors, ideas, or discourse, but seldom by their interaction.

The Integrative Model of Policy Change is positioned explicitly to bridge this fragmentation.

3. Ontological and Epistemological Assumptions

Ontologically, the model conceives policy as a socially constructed and relational phenomenon, embedded in political, economic, social, technological, and environmental contexts. Policies are not static objects but evolving configurations of meaning, power, and practice. Epistemologically, the model adopts a post-positivist and interpretive stance, recognizing that policy problems, solutions, and outcomes are shaped through narratives, argumentation, and interaction rather than discovered through purely technical analysis.

4. The Integrative Model of Policy Change

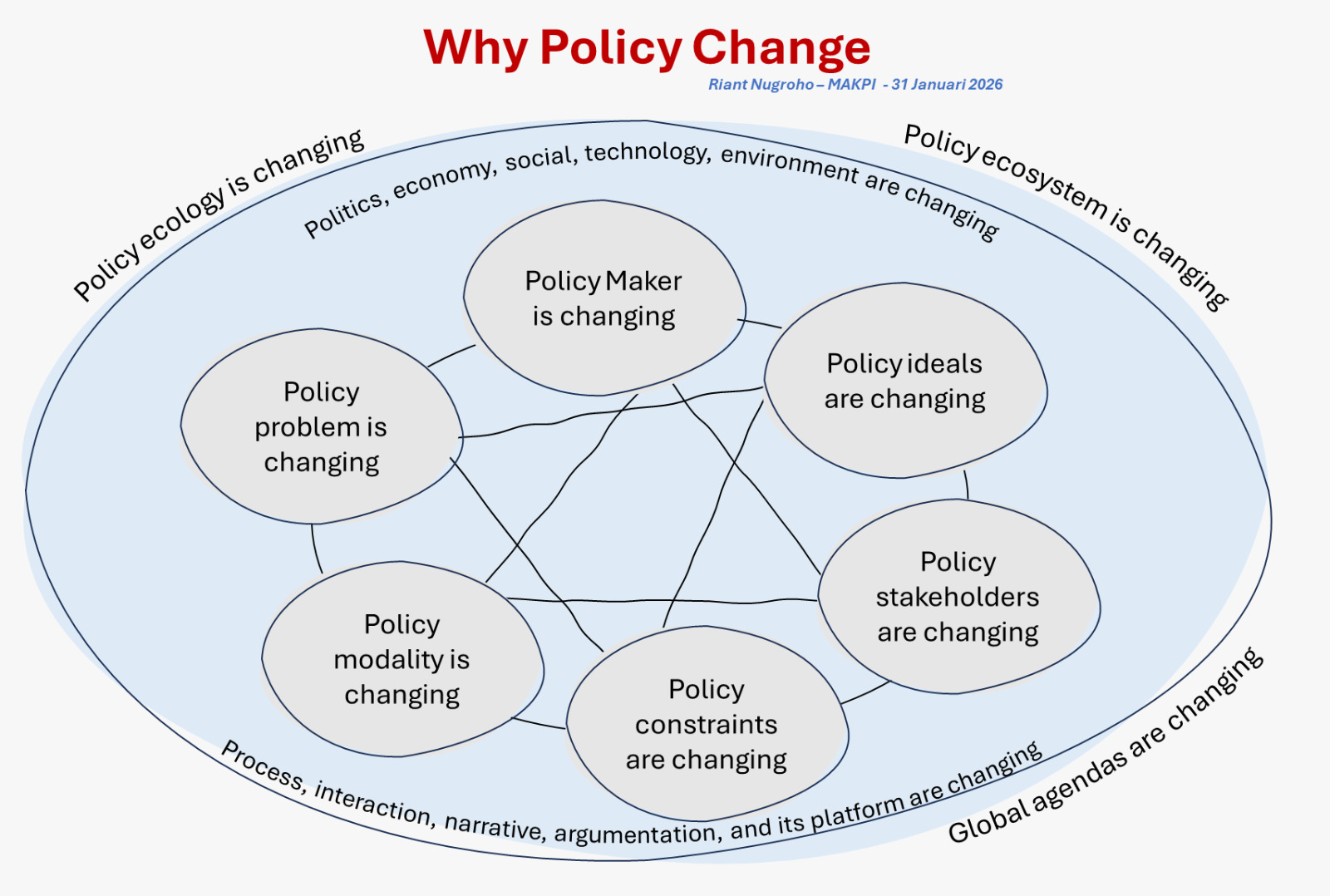

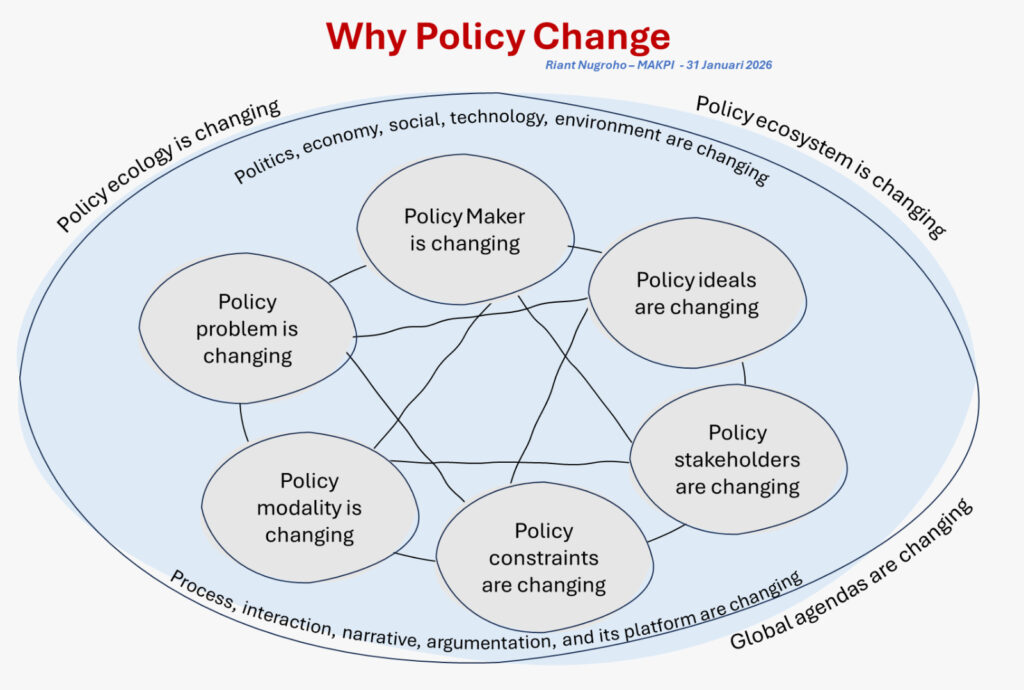

The model we proposed here consist of three interrelated analytical layers: macro, substantive, and process-discursive.

4.1 Macro Contextual Layer

At the outermost layer lies the policy environment: politics, economy, social structures, technological change, and environmental conditions. These elements correspond to what Sabatier and Weible (2014) describe as external perturbations—contextual changes that destabilize existing policy equilibria. Crucially, contextual change does not directly determine policy outcomes; rather, it creates conditions of uncertainty and contestation within which policy change becomes possible.

4.2 Substantive Policy Layer

Within this environment, policy change occurs through transformations in six substantive elements: (1) Policy problems, which are socially constructed and reframed (Kingdon, 2014; Edelman, 1988); (2) Policy ideals or paradigms, reflecting shifts in normative and cognitive beliefs (Hall, 1993); (3) Policy makers, whose preferences and interpretive frames shape decisions (Peters, 2015; Fischer, 2003); (4) Policy stakeholders, whose changing configurations reflect networked governance and discourse coalitions (Rhodes, 1997; Hajer, 1995); (5) Policy constraints, including fiscal, legal, and political limits (Wildavsky, 1979); (6) Policy modalities or instruments, which evolve alongside governance practices (Salamon, 2002).

These elements interact non-linearly: change in one dimension often reverberates across others.

4.3 Process–Discursive Layer

The most distinctive contribution of the model lies in its third layer: the process–discursive arena. This includes changes in policy processes, interaction patterns, narratives, argumentation, and the platforms through which policy debates unfold.

Following Hajer’s argumentative turn, policy-making is understood as a process of persuasive interaction rather than purely rational choice. Edelman’s work highlights how symbols and narratives structure public understanding, while Fischer emphasizes deliberation as a site of contestation over meaning and legitimacy.

Importantly, contemporary policy processes are increasingly mediated by digital and media platforms, which shape visibility, participation, and authority within policy debates (Dryzek, 2010). Platforms are not neutral channels; they actively structure the dynamics of policy change.

5. Mechanisms of Policy Change

The model identifies three core mechanisms through which policy change occurs: first, reframing, whereby dominant narratives redefine problems and solutions; secondly, reconfiguration, involving shifts in actors, coalitions, and power relations; and thirdly remediation, in which changes in instruments and platforms alter how policy is enacted and perceived. Policy change becomes most likely when these mechanisms operate simultaneously across layers.

6. Contributions and Implications

The Integrative Model of Policy Change offers several contributions. It bridges structural, agential, and discursive explanations of policy change. It conceptualizes policy change as a process of meaning-making and performance, not merely decision-making. It incorporates digital platforms as structural elements of contemporary policy processes. It provides an analytically flexible framework applicable across policy sectors and political contexts.

7. Conclusion

Policies change not simply because problems worsen, leaders rotate, or institutions reform, but because the conditions under which policy meanings are constructed and contested evolve. By integrating context, substance, and process into a single analytical framework, the Integrative Model of Policy Change provides a more comprehensive explanation of why policies change—and why they often change in unexpected ways.